By Melissa Siebert

Sit among the bleached, ruined, dry-packed walls and fallen stones where the royal woman once gave birth. Stand where the king used to survey his lands and his people. Gaze across the Luvuvhu and Limpopo rivers into Zimbabwe and Mozambique. Let the stones of Thulamela tell their story of a once-prosperous, hierarchical community where everything had its place. This World Heritage Site in the Pafuri Section of Kruger was part of a culture also represented by two other “lost kingdoms”, Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe. All three shared similar socio-economic structures and the iconic towering, mortarless stone walls. Thulamela outlived these other two kingdoms, and possibly “inherited” some of the people who abandoned Great Zimbabwe in the 15th century. At Thulamela 500 royals lived on top of the citadel; 1500 commoners lived down below, farming sorghum and millet in the fertile soil, mining iron ore in 200 or so local mines and trading with Arab and Portuguese merchants. Local ivory, gold and animal skins were traded for goods from as far away as India and China. Slaves were sadly also part of the local trade, raided by Arab traders and brought to the coast of what is now Mozambique. What happened to the people of these kingdoms, the ancestors of today’s Venda and Shona people, is still being debated by archaeologists and others. “Thulamela was burned down by the people who lived here, the Venda themselves,” Said guide Eric Maluleke, leading the way up the steep, rocky path to the top of the citadel on an early summers day. “There was too much tsetse fly and drought.” This is one explanation. Others have tied the kingdom’s demise to the death of the king, the takeover of Indian Ocean trade by the Portuguese, conflict over land and other resources. Whatever the cause, the Thulamelans dispersed throughout Southern Africa, but left behind testaments to the sophistication of earlier African cultures. The site, seemingly untouched for three-and-a-half centuries, has been proclaimed as one of the most significant Late Iron Age sites on the continent. “People outside knew the ruins were here” Eric said at the hard-won citadel summit, settling us on some stones under a massive, ancient baobab in a magnificent grove. “But they were afraid to come. It was overgrown, it felt like trespassing.” Behind us, to the west and north, loom the massive stone walls, the high exterior walls concealing shorter interior ones. They are almost in ruins, periodically dismantled by local baboons searching for scorpions and assembled again by humans. Maluleke spent his first year at Thulamela as a stonemason on the site, rebuilding walls initially constructed in 1500AD. “In Zimbabwe culture, they’d send a team ahead to find a place for settlement,” Eric explained. “The place should be a raised place, flat on top with big trees, water nearby and land to cultivate.” Thulamela fitted the bill. “we’ve found gold amulets, foil and beads,” said Eric, stepping nimbly over loose stones and low walls, remarking that a number of Thulamelans were goldsmiths. “We also found a lot of copper. The women used to wear up to five kilos of copper. We’ve found hunting spears, ostrich egg beads, glass beads from India, Porcelain from China and a double iron gong, possibly from Central or West Africa, the chief’s musical instrument.” Two human skeletons were uncovered in 1996, exhumed and since reburied on the site. “One as a woman, a queen, 45 to 55 years old and buried in the foetal position inside a hut,” Eric said, showing us her resting place. Queen Losha. They named her that because of the position of her hands, palms together under her left temple, a sign of respect. DNA testing revealed she was buried, along with 291 gold beads, a gold bracelet on her left arm and a copper wire on her legs, in about 1600 AD.” The second skeleton was that of a male buried roughly 170 years earlier than Queen Losha, facing west, as they all were, to optimise the glorious sunsets. He was a chief, probably a relative of the king, speared through the spinal cord and buried in a packed position with 73 gold beads and 990 ostrich egg beads. “The day we found him there was a leopard lurking nearby, so we named him King Ingwe.” The King’s quarters were designed to keep him hidden from everyone except his closest advisers, but with slots for the king to peer out. Eric pointed to a series of sharp stones like a crocodiles tail. “This is where the kings messenger and diviner stood to screen people. You’d be fined, with cattle, gold or cowrie shells, if you went to the king without permission.” We walked past a granary with grinding stones and several tall stones monoliths to protect the community. An enclosure where the Dombe or snake dance was once performed. A workshop with sharpening stones, to hone spears, another where the women made clay pots, and the ancient maternity ward. Standing on the edge of the cliff, surveying the vast floodplains and an old elephant trail down below, you can feel it: Thulamela lives.

From the Wild Magazine summer 2012/2013

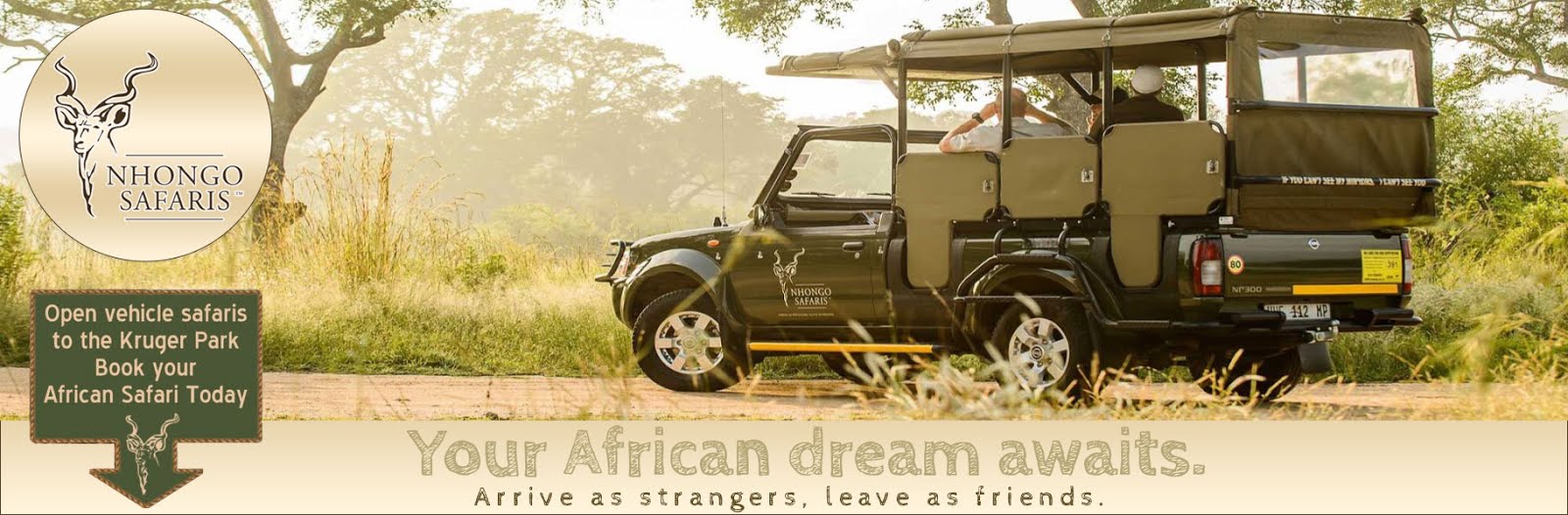

Verity and Dean Cherry had an African dream in 1999 and started Nhongo Safaris® to eliminate the logistical challenges of international visitors on safari. We provide a once in a lifetime experience for wildlife enthusiast that demand quality overnight safaris in South Africa and most particularly the Kruger National Park. We want to enrich our visitors’ experience by providing Luxury Safari Packages or African Safari Holidays and maintain our position as leader in Kruger Park Safaris.

Featured post

Some of Nhongo Safaris Fleet of Open Safari Vehicles

The photo shows some of our fleet of Open Safari Vehicles used while on safari in the Kruger National and Hwange National Parks. These ve...

No comments:

Post a Comment