The track he took was merely the scorings made by skidding wagons coming down the mountain; it was so steep and rough there that a pull of ten yards between the spells for breath was all one could hope for; and many were thankful to have done much less. At the second pause, as they were passing us, one of his oxen turned, leaning inwards against the chain, and looked back. Old Charlie remarked quietly, "I thought he would chuck it; only bought him last week. He's got no heart." He walked along the span up to the shirking animal, which continued to glare back at him in a frightened way, and touched it behind with the butt of his long whip-stick to bring it up to the yoke. The ox started forward into place with a jerk, but eased back again slightly as Charlie went back to his place near the after-oxen. Once more the span went on and the shirker got a smart reminder as Charlie gave the call to start, and he warmed it up well as a lesson while they pulled. At the next stop it lay back worse than before. Not one driver in a hundred would have done then what he did: they would have tried other courses first. Charlie dropped his whip quietly and outspanned the ox and its mate, saying to me as I gave him a hand: "When I strike a rotter, I chuck him out before he spoils the others!" in another ten minutes he and his stalwarts had left us behind. Old Charlie knew his oxen--each one of them, their characters and what they could do. I think he loved them too; at any rate, it was his care for them that day--handling them himself instead of leaving it to his boys--that killed him. Other men had other methods. Some are by nature brutal; others, only undiscerning or impatient. Most of them sooner or later realise that they are only harming themselves by ill-treating their own cattle; and that is one--but only the meanest--reason why the white man learns to drive better than the native, who seldom owns the span he drives; the better and bigger reasons belong to the qualities of race and the effects of civilisation. But, with all this, experience is as essential as ever; a beginner has no balanced judgment, and that explains something that I heard an old transport-rider say in the earliest days-- something which I did not understand then, and heard with resentment and a boy's uppish scorn. "The Lord help the beginner's boys and bullocks: starts by pettin', and ends by killin'. Too clever to learn; too young to own up; swearin' and sloggin' all the time; and never sets down to _think_ until the boys are gone and the bullocks done!" I felt hot all over, but had learned enough to keep quiet; besides, the hit was not meant for me, although the tip, I believe, was: the hit was at some one else who had just left us--one who had been given a start before he had gained experience and, naturally, was then busy making a mess of things himself and laying down the law for others. It was when the offender had gone that the old transport-rider took up the general question and finished his observations with a proverb which I had not heard before--perhaps invented it: "Yah!" he said, rising and stretching himself, "there's no rule for a young fool." I did not quite know what he meant, and it seemed safer not to inquire. The driving of bullocks is not an exalted occupation: it is a very humble calling indeed; yet, if one is able to learn, there are things worth learning in that useful school. But it is not good to stay at school all one's life. Brains and character tell there as everywhere; experience only gives them scope; it is not a substitute. The men themselves would not tell you so; they never trouble themselves with introspections and analyses, and if you asked one of them the secret of success, he might tell you "Commonsense and hard work," or curtly give you the maxims `Watch it,' and `Stick to it'--which to him express the whole creed, and to you, I suppose, convey nothing. Among themselves, when the prime topics of loads, rates, grass, water and disease have been disposed of, there is as much interest in talking about their own and each other's oxen as there is in babies at a mothers' meeting. Spans are compared; individual oxen discussed in minute detail; and the reputations of `front oxen,' in pairs or singly, are canvassed as earnestly as the importance of the subject warrants--for, "The front oxen are half the span," they say. The simple fact is that they `talk shop,' and when you hear them discussing the characters and qualities of each individual animal you may be tempted to smile in a superior way, but it will not eventually escape you that they think and observe, and that they study their animals and reason out what to do to make the most of them; and when they preach patience, consistency and purpose, it is the fruit of much experience, and nothing more than what the best of them practise.

Verity and Dean Cherry had an African dream in 1999 and started Nhongo Safaris® to eliminate the logistical challenges of international visitors on safari. We provide a once in a lifetime experience for wildlife enthusiast that demand quality overnight safaris in South Africa and most particularly the Kruger National Park. We want to enrich our visitors’ experience by providing Luxury Safari Packages or African Safari Holidays and maintain our position as leader in Kruger Park Safaris.

Featured post

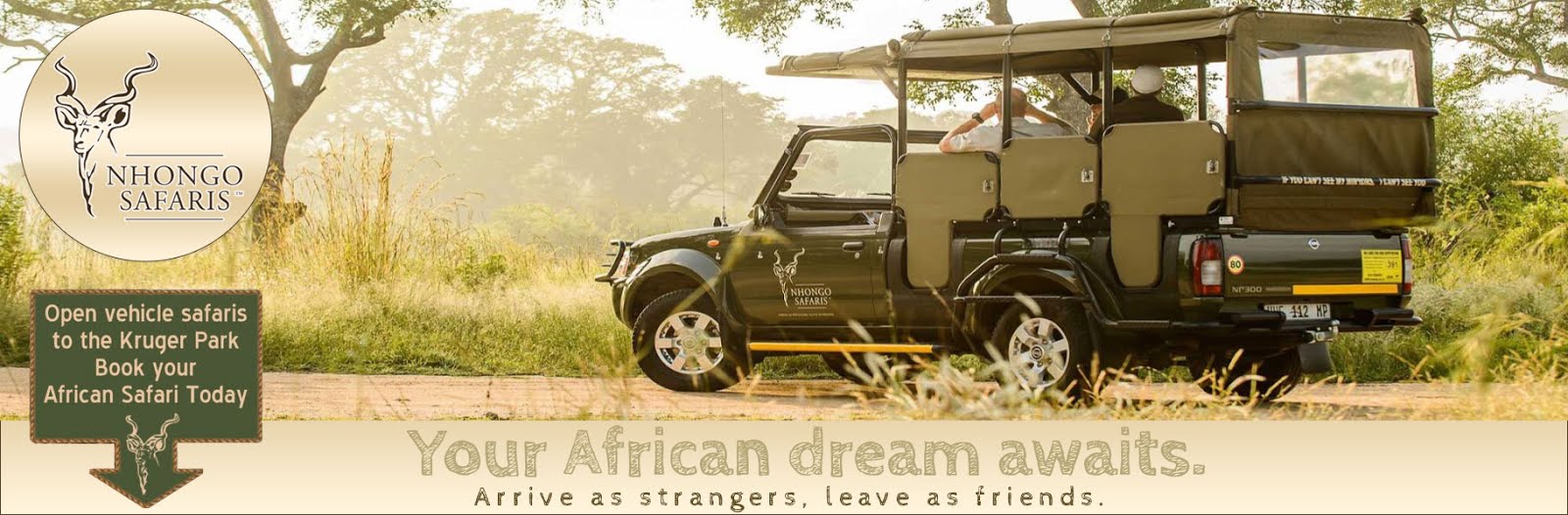

Some of Nhongo Safaris Fleet of Open Safari Vehicles

The photo shows some of our fleet of Open Safari Vehicles used while on safari in the Kruger National and Hwange National Parks. These ve...

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment